COP29 in Baku will decide the future of global climate finance. As developing nations demand $1 trillion in annual support, tensions rise over who should contribute and how funds are allocated. Will this summit deliver on the promise of climate justice and equity?

The global climate summit in November in Baku, Azerbaijan, has been dubbed the “climate finance COP,” because its most important decision must be an agreement on a New Collective Quantified Goal on climate finance (NCQG) starting in 2025. This will replace the existing, wholly inadequate USD 100 billion annual target set in 2009. The new goal’s commitment to deliver significantly more and qualitatively better climate finance will be the litmus test for whether the promise of the Paris Agreement can still be achieved. Can all countries, irrespective of differentiated capabilities and responsibilities, act jointly and decisively to ratchet up ambition in climate actions every five year to keep global warming to 1.5 degree Celsius? At issue at COP29 is nothing less than whether the deal struck in Paris in 2015 still holds: developed countries providing financial support to developing countries in return for their increased climate efforts. And with it, the future of climate justice and equity in the multilateral climate regime.

After last year’s Global Stocktake at COP28 in Dubai highlighted the insufficiency of current collective climate efforts, the NCQG outcome in Baku – especially its quantum or scale – will send a strong message to developing countries. Many of them are trapped in a vicious cycle of indebtedness and persistent poverty and affected by ever more devastating climate impacts. How much ambition they can afford in their new nationally determined contributions (NDCs) due to be delivered in 2025 will depend on the NCQG. Already in the past, many of the climate commitments that developing countries outlined in their initial round of national climate action plans five years earlier were conditional on getting adequate financial support that is not drawing from official development assistance (ODA), but new and additional to ODA and other official finance flows.

The mandate for setting a new climate finance goal “from a floor of USD 100 billion per year, taking into account the needs and priorities of developing countries” was already enshrined in the decision that approved the Paris Agreement in 2015. Efforts to determine the new goal were kicked off at COP26 in Glasgow for a three-year process that combined technical expert meetings allowing for broad stakeholder and observer input (eleven held so far geographically spread out) with political guidance through annual high level ministerial meetings. They ramped up in 2024 with negotiation sessions convened under an ad hoc work program with the goal to develop the structure and core elements of a decision text with iterations – including a new version released just before COP29 – that will see fierce negotiations at Baku - if the NCQG can be agreed to at all.

Indeed, the discussions for a new goal have been extremely contentious, pitting developed and developing countries with seemingly irreconcilable positions against each other. Despite three multi-day negotiation sessions already conducted this year, and iterative versions of new draft texts in response to negotiators’ feedback, so far there have been few if any indications of what a bridging proposal or compromise could look like. Two consultations at ministerial level this fall in New York and Baku did little to move the discourse forward. Nor is it clear if a compromise is even desirable, especially for developing countries for whom the most is at stake, if it delivers the lowest common denominator of what is acceptable to all negotiation parties.

At the heart of the controversial discourse with no solution in sight is not only the overall scale of the new goal, but efforts to answer the fundamental questions of who should be mandated to contribute to it, who should receive money, and for what. At issue is also whether in setting a new goal the lessons learned from the previous USD 100 billion annual target are applied to address its shortcomings, such as by looking not just at the quantity but also the quality of climate finance provided to developing countries, specifically how easy or difficult it will be to access finance or how concessional the funding will be.

Push to expand the contributor base…

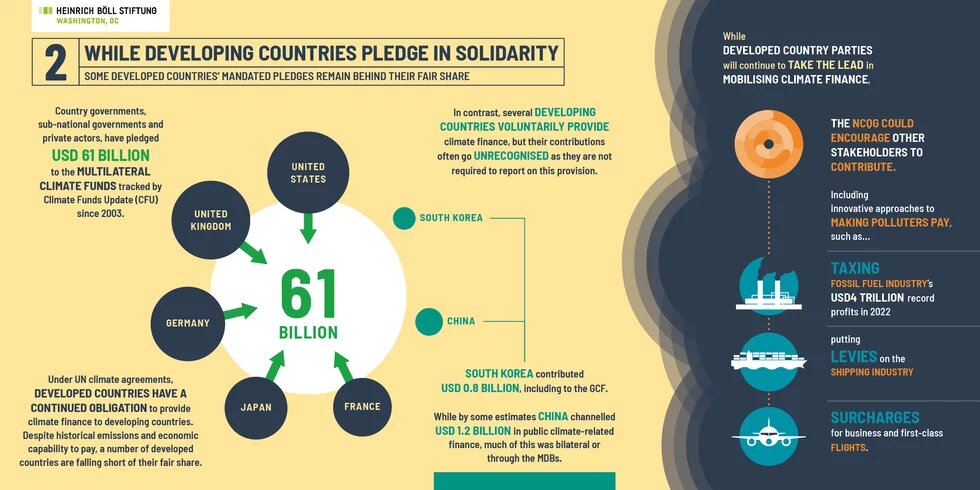

Developing countries see the push by developed countries to expand the contributor base of countries that should be mandated to contribute to the NCQG as undermining the core principle of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) adopted in 1992. It acknowledges the common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities (CBDR-RC) of developed and developing countries and the need for equity by taking into account the historical responsibility of industrialized countries as major emitters of greenhouse gases under a polluter-pays understanding (as enshrined in annexes listing countries with differentiated responsibilities) and the related mandate under the Convention for industrialized countries (23 countries listed under its Annex II) to financially support developing countries. They insist that the principles of equity and CBDR-RC are applicable to the NCQG as they understand the Paris Agreement to be under the Convention, and therefore reject any obligation of countries still listed as developing countries under the Convention (such as China and other emerging economies) to be mandated to pay for the NCQG.

Developed countries, on the other hand, dispute that the Paris Agreement is under the Convention and bound by its annexes differentiating countries’ obligations. They point to their own financial difficulties and the enormous amount of support needed, and argue that a number of emerging economies, primarily China and fossil fuel producing countries in the Gulf region with their growth in wealth and accumulation of aggregated emissions over the past 30 years, should be compelled to contribute to the NCQG. Several developed countries, including prominently Canada and Switzerland, proposed potential criteria such as per capita income or either accumulated or per capita emissions in technical submissions. Switzerland would like countries other than developed countries that “are among the ten largest current emitters and have a purchasing power parity adjusted gross national income per capita of more than $22,000” to also pay. This formula would bring Russia, Saudi Arabia and possibly China into the pool of mandated climate finance contributors. In contrast, research using different criteria, including looking at historic emissions, would exclude China and other populous high emitting emerging market economies, arguing that their responsibility and financial capacity on a per capita basis remains much lower than most developed countries’, despite China’s status as today’s second-largest economy and top annual global emitter.

Rather than distract from the continued obligations of developed countries, the decision for a new NCQG can invite all other countries to do more, and account in the future better for contributions of those countries willing to heed the call. Under the Paris Agreement, other countries “in a position to do so” are already encouraged to voluntarily provide finance as well, and indeed a number of countries have done so. The United Arab Emirates is an example: it has supported the new Fund for responding to Loss and Damage (FRLD). South Korea is another, as a long-time contributor to repeated replenishment rounds of the Green Climate Fund (GCF). A recent analysis has found that by some measures China, between 2013 and 2022, voluntarily provided and mobilized USD 45 billion to support climate actions in developing countries, adding up to an estimated 6 percent of the total climate finance from developed countries in the same period.

Source: 10 Things to Know about Climate Finance: NCQG Edition 2024

… with efforts to limit recipients

Developed countries’ push for expanding the contributor base is matched by their efforts, often phrased as calls for more making climate finance ”more effective”, to narrowly target limited public finance support to the countries they see as the most vulnerable. This is focused on least developed countries (LDCs), small island developing states (SIDS), and fragile and conflict afflicted states. The latter is a country categorization not found in the UNFCCC, which only recognizes the special circumstances of SIDS and LDCs, and is viewed with suspicion by many developing countries as an attempt to divide them with the promise of prioritized support or minimum allocation targets. This has led in the past to tensions, with the potential to disrupt the unity of developing countries in the NCQG negotiation end phase. This would be a move from the playbook developed countries also used in the design process for the new loss and damage fund last year. The eligibility of all developing countries to receive financial support is of course a core principle of the UNFCCC and Paris Agreement.

What’s in a number

So far, only developing countries have put forward a concrete number for the scale of the NCQG, which they argue must focus on public finance provided and mobilized from developed to developing countries. Several developing country groups including Arab states and the African group have suggested an annual amount between USD 1 to 1.3 trillion, roughly ten times the amount of the current goal which ignores both expressed needs and scientifically established necessity. This scale of public support by the Global North under the NCQG is supported by civil society, who points out that the actual climate debt owed to countries of the Global South is much higher. These asks, if funding the full amount were to start in 2025, are roughly in line with the cost estimates of USD 5 to 6.9 trillion for implementing developing countries’ nationally determined contributions (NDCs) by 2030 according to a new UNFCCC Needs Determination Report (NDR2) by its Standing Committee on Finance (SCF).

The actual needs are undoubtedly much greater, as the NDR2 only reflects costed NDCs (only about half of the identified 5,760 needs reported by 98 developing countries include cost calculations) and many NDCs do not yet sufficiently reflect planned adaptation actions and efforts to address loss and damage, let alone figures for the funds needed to implement them. In their Global Stocktake of progress in implementing the Paris Agreement at COP28, countries confirmed the enormous financial efforts required for closing the growing gap between the needs of developing countries and the funding provided to them. For adaption by some estimates between USD 215 and 387 billion annually up until 2030 are required. Addressing escalating losses and damages could cost up to USD 671 billion per year by 2030. And to reach net zero emissions by 2050, about USD 4.3 trillion per year needs to be invested in clean energy up until 2030, increasing further to USD 5 trillion per year up until 2050.

Developed countries acknowledge that there needs to be a core of public finance provision in the NCQG, but are mum about how large that core should be. Their argument, forcefully pushed by the United States, is that climate finance at the scale required can only be reached if the NCQG is structured as a multi-layered global investment goal. This goal would not only include all private sector investments in clean energy or resilience measures globally (the overwhelming majority of which continues to be concentrated in rich countries and few emerging market economies), but also all domestic efforts, including those that developing countries are already undertaking – despite the absence of adequate support from rich countries for adaptation and for addressing loss and damage. This would make the quantum bigger, no doubt, but without necessarily substantively increasing the scale of support from rich countries to those that need it most. The inherent climate injustice is obvious: developing countries are already paying with lost economic growth and development for climate impacts to which they have contributed significantly less than developed countries, which have profited from fossil-fuel driven economic growth up to a century longer. Take for example the 55 most climate-vulnerable countries (V20), which have calculated that they lost USD 525 billion, or a fifth of their countries’ GDP, between 2000 and 2019 from climate change. Their combined population of 1.74 billion people (a fifth of the world’s population) only accounts for 4 percent of global emissions.

There have been efforts to calculate the climate debt owed to developing countries by developed countries, including compensation for the appropriation of the majority of the remaining global carbon budget, if the world tries to stay at 1.5 degree Celsius warming. One 2023 study shows that by 2050 the Global North will owe USD 192 trillion in reparations to the countries of the Global South, or around USD 5 trillion annually.

These numbers put the actual NCQG asks of developing countries for around USD 1 trillion in annual public support by developed countries into context, especially in light of a global financial and economic system favoring developed countries, for example in the cost of access to capital or the ability to run deficits. By some calculations, the global economic architecture extracts per year about USD 2 trillion in net financial flows from the Global South to the Global North.

The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report has articulated that there is sufficient global capital and financial liquidity to address global climate finance gaps, but the redirection of finance toward climate action and support for developing countries is required as a matter of political will and climate justice. Stopping fossil fuel subsidies and redirecting military spending, which reached USD 2.4 trillion in 2023, taxing fossil fuel extraction based on the polluter-pays principle through a Climate Damages Tax or introducing a Global Wealth Tax must be considered to generate the new and additional climate support required without cannibalizing official development assistance.

Structure and timeframe matter, too

Regarding the structure of the new goal, countries also disagree about whether and how to include finance for addressing loss and damage. An NCQG based on needs and science, given the reality of escalating impacts, should include it, ideally as a sub-goal and third thematic finance pillar on equal footing with finance provision for mitigation and adaptation. This is the view of developing countries and civil society observers, whose forceful push for such funding support resulted in the COP28 decision that set up the new Fund for responding to Loss and Damage (FRLD) as a core channel of the financial mechanism of the UNFCCC and Paris Agreement, structurally on par with the GCF and the Global Environment Facility (GEF). Rich countries reject any inclusion of loss and damage under finance commitments in the NCQG, pointing out that the mandate for finance provision in the Paris Agreement, under which the NCQG is negotiated, as well as the existing goal, exclude loss and damage support.

The question of how quickly the scale of the NCQG would be reached, if agreement at COP29 can be found, adds another layer. Developing countries want the NCQQ as a goal of public finance provided and mobilized to start in 2025, while developed countries, such as those of the European Union, see the goal of scaling up from the current base to a target amount at the earliest by 2035. This is reminiscent of the USD 100 billion goal set in 2009 which likewise allowed for a ten+ year scale up period to be reached by 2020. The old goal was set without targets for financing milestones to be reached along the way, limiting accountability and delaying its achievement. This should not be replicated in the NCQG.

Adequate quantity needs quality

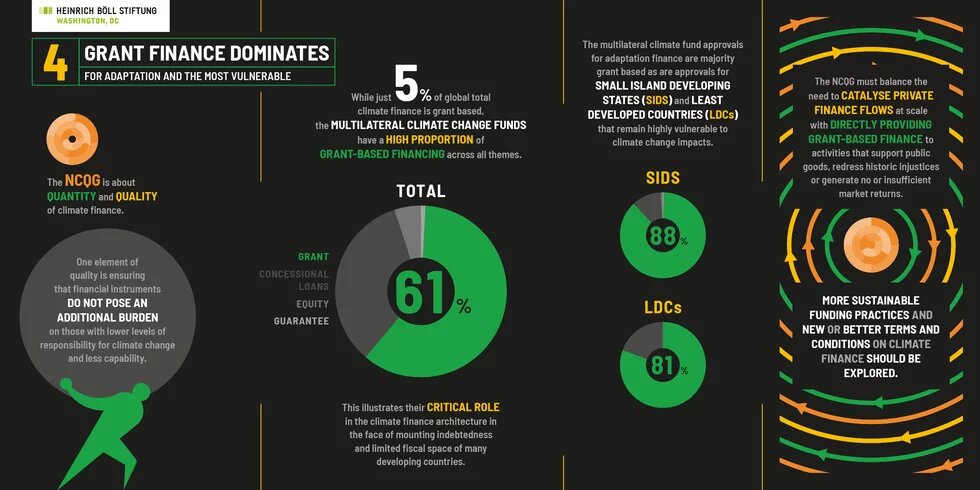

One of the core lessons learned from the existing USD 100 billion goal is the necessity to include qualitative criteria in a determination of the NCQG, and this requires a clear understanding of what is counted as climate finance and how. The USD 100 billion were for example only accounted for in nominal terms – meaning the face value of finance provided, irrespective of its concessionality and delivery as grants or as loans, with a significant share of loans at market rates even counted as climate finance support. Developing countries thus see the NCQG negotiations as an opportunity to highlight the need for a uniformly accepted definition of climate finance. While the climate regime’s SCF has a working definition of what constitutes climate finance, and updated it just this year, it remains vague and allows essentially a bottom-up, provider country-based determination that developed countries defend as the corollary to the NDCs as bottom-up climate action plans. If any progress can be made in Baku on the issue of climate finance definition, it would most probably consist of a type of exclusion list. This could cover some financing practices, such as counting market rates loans or money provided through expert credit agencies as climate finance provided, especially since the latter is given with the sole purpose of soliciting goods and services from the country providing the support. Such kind of ‘tied’ climate finance currently exists at a surprising scale, as some investigative reporting revealed.

According to the latest OECD assessment on progress towards the 100 billion goal, reached in 2022 for the first time, some 69 percent were loans of varying concessionality, including for a large share of adaptation actions, which received some 28 percent of public climate finance. Most loans were delivered through multilateral development banks (where 90 percent of the finance delivered was as loans), while grant support was greater in dedicated multilateral climate funds like the Adaptation Fund or the GCF (providing the majority of their funding as grants), stressing their importance for highly concessional climate finance delivery, especially as more and more developing countries are facing unsustainable debt levels.

Source: 10 Things to Know about Climate Finance: NCQG Edition 2024

As highlighted by a 2022 UNDP report, more than half of the 54 most indebted developing countries are also ranked amongst the most climate vulnerable countries; and almost all these countries are paying now four times in external debt service payment of what they had to pay in 2010. This undercuts their ability to support adaptation or address loss and damage with domestic resources, let alone hit key sustainable development targets and reduce poverty. The concessionality of climate finance is thus also intrinsically linked to human rights and gender-responsiveness, as women’s traditional and unpaid care burden is aggravated in the face of worsening climate impacts, especially when the lack of fiscal space in recipient developing countries means that the strengthening of social protection systems, which is so necessary for building the resilience of the population, cannot take place. Quantitative targets for providing the bulk of finance as grants – and exclusively for adaptation and for addressing loss and damage – and for increasing the share of climate finance flowing through multilateral climate funds, the mandate to take into account debt sustainability in climate finance provision and a call to action for comprehensive debt relief –including substantial debt cancelation through a ‘climate jubilee’ – should therefore be reflected in the NCQG. It is not enough to instead suggest that debt-for-climate-swaps, which are limited, cumbersome to negotiate and administrate, and less efficient than conditional grant support, or climate resilient debt clauses, which suspend repayment after climate disasters temporarily, could provide the needed relief and expanded fiscal space to developing countries.

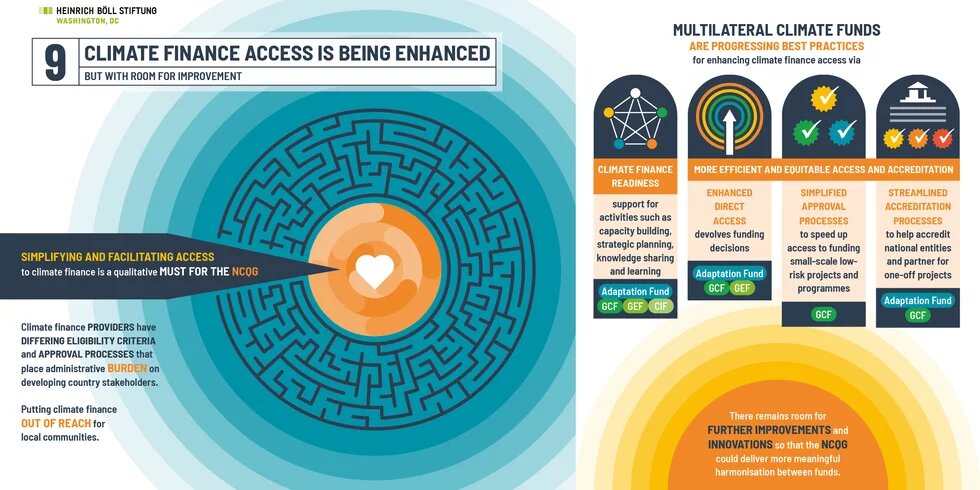

Enhancing access and subsidiarity

Much of the gains of a substantial increase in the quantity of climate finance provided and mobilized will be curtailed if not accompanied by increasing and facilitating access to climate finance, including through mandates to providers to simplify or reduce access requirements, such as co-financing mandates and comprehensive climate data and ‘climate rationale’ justifications for funding support. A core benchmark for the increased quality of climate finance support under the NCQG will be its commitment to scale up and prioritize direct access modalities for developing countries’ own regional, national, and sub-national institutions. This must include significantly expanding opportunities for devolved decision-making of climate finance at the most local level feasible. Applying subsidiarity as a core qualitative principle to the NCQG would mandate enhancing direct access to climate finance by the most affected. These people are often marginalized groups and communities, and climate finance must support locally-led approaches that correspond to the needs and priorities of women and gender-diverse people, children and youth, Indigenous Peoples, people living with disabilities, climate migrants or workers on the frontlines of the climate crisis, because they are crucial participants and implementers in climate action.

Creating accountability and transparency by setting a quantitative minimum target for such locally accessible and devolved finance in the NCQG reached either annually or as a progression over time, and regular mandated reporting against it, would be an important step forward. The existing USD 100 billion goal has no such mandate. A similar target could be considered to track and account for providing and increasing the share of gender-responsive finance. Such technical targets must be informed and guided by a human-rights based approach and framing for the NCQG that mandates a funding mechanism to improve their governance and practices by interacting with beneficiary groups and communities as rightsholders, not just with banks and ministries of finance as clients.

Source: 10 Things to Know about Climate Finance: NCQG Edition 2024

Principled operationalization, not preamble promise

While there is some acknowledgement of the importance of direct funding provision to local communities and the gender-responsiveness of finance and some support by negotiating countries, anchoring such qualitative elements in the NCQG decision as concrete operational commitments to be tracked and reported on regularly in an improved transparency framework for the NCQG, rather than just as visionary ‘calls for action’ without much enforcement teeth, will be challenging. It will be similarly instructive to see whether and where explicit human rights language can be placed in an NCQG decision.

Human rights, in particular the rights of the poorest and most vulnerable people and communities facing the disproportionate burden of the climate crisis, and core principles of equity, climate justice, CBDR-RC, historical responsibility, right to development, just transition and intergenerational justice cannot just be mentioned as the illustrative context or the preamble for the new climate finance goal. They must determine its quantitative and qualitative elements and be enshrined as operational mandates and commitments with clear responsibility and accountability throughout the decision text. The new goal must also allow for the review and regular revision of its adequacy in line with the evolving needs in light of new scientific findings and as part of the efforts of the Paris Agreement to ratchet up collective climate action over time. Only then will the new climate finance goal be fit-for-purpose to confront the climate emergency and provide the new, additional, predictable, and adequate support to the people in the Global South that they deserve and are owed.

This article first appeared here: us.boell.org